Welcome to the Central Trade Authority wiki. This page contains all information I've written for the worldbuilding project.

The Central Trade Authority is a pseudo-governmental and highly bureaucratic organization that grew out of a postwar era from a demand for order and no stable governments after the war ended. It was intended as a temporary solution to badly managed and fragile systems and stuck around because no other powers were as organized or powerful as they were/are. Their current goal is to cling on to power as long as possible, but its authority now relies more on bureaucratic habit and paperweight regulation than genuine control.

GOALS

Figure out more to write...

TO-DO

add better visuals

replace the banner image

design the CTA's emblem

design SEVRA uniforms, etc.

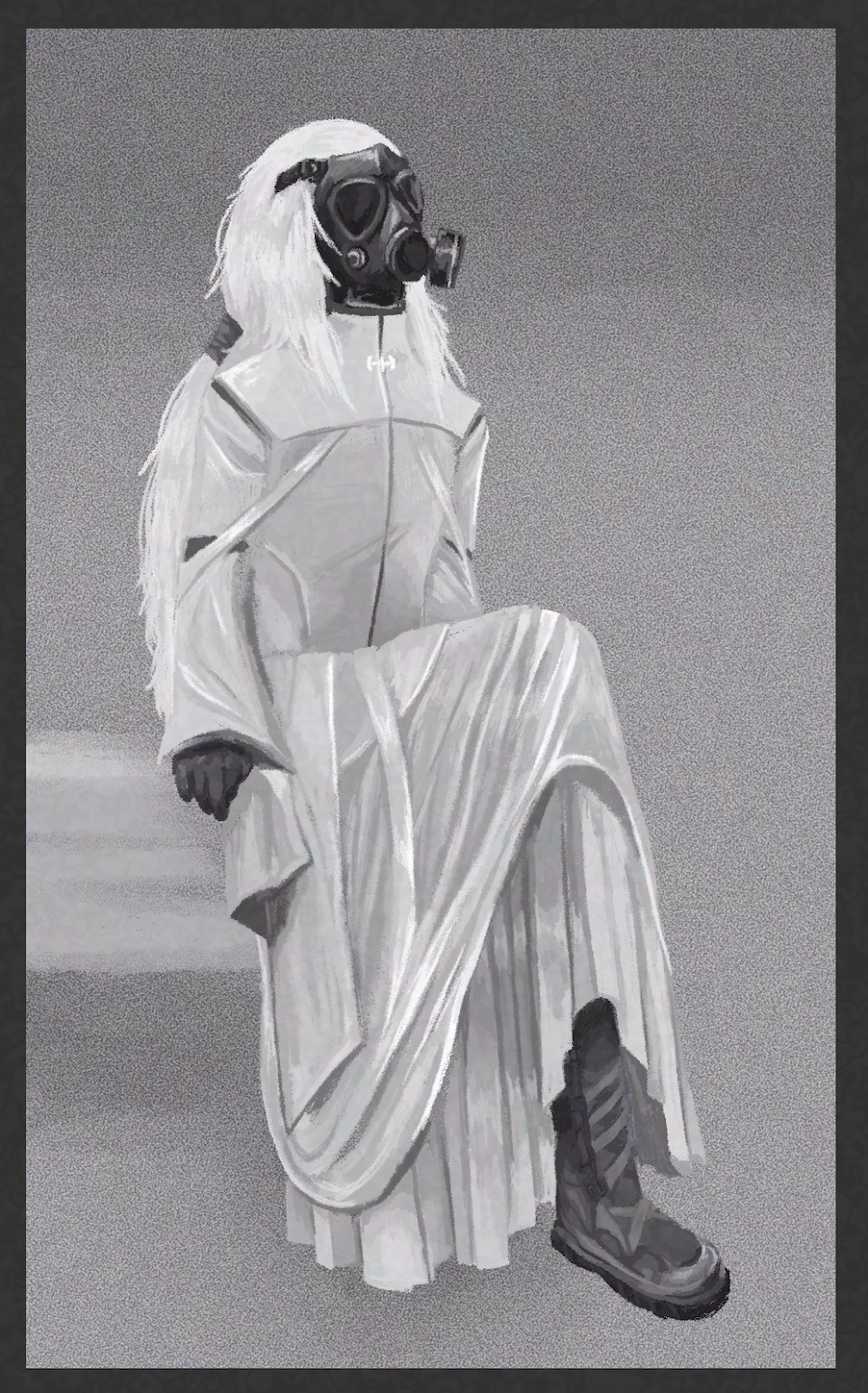

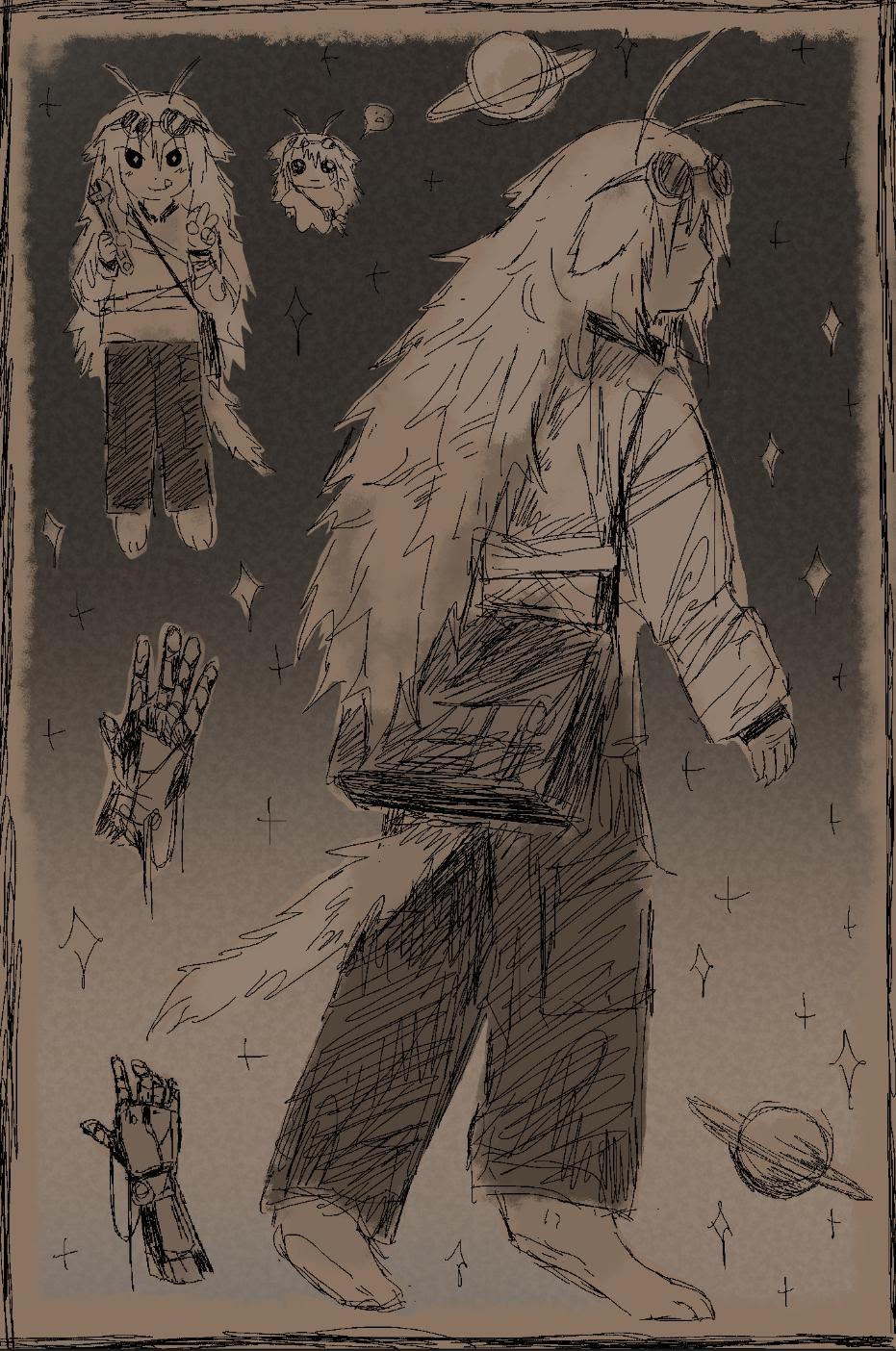

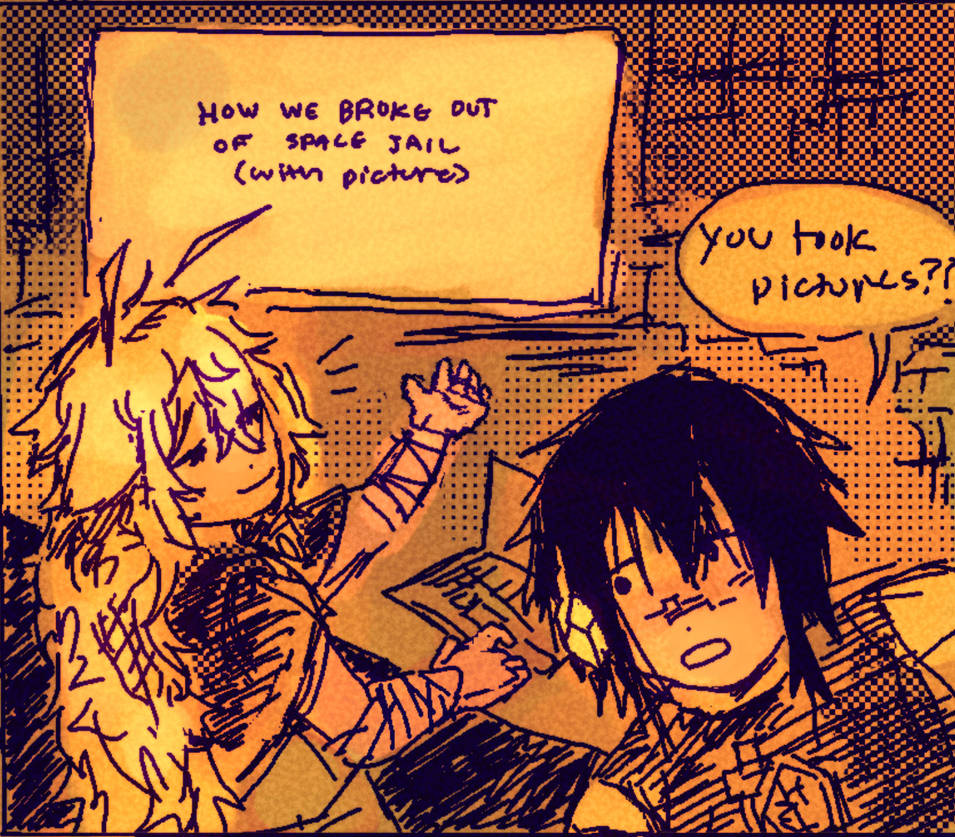

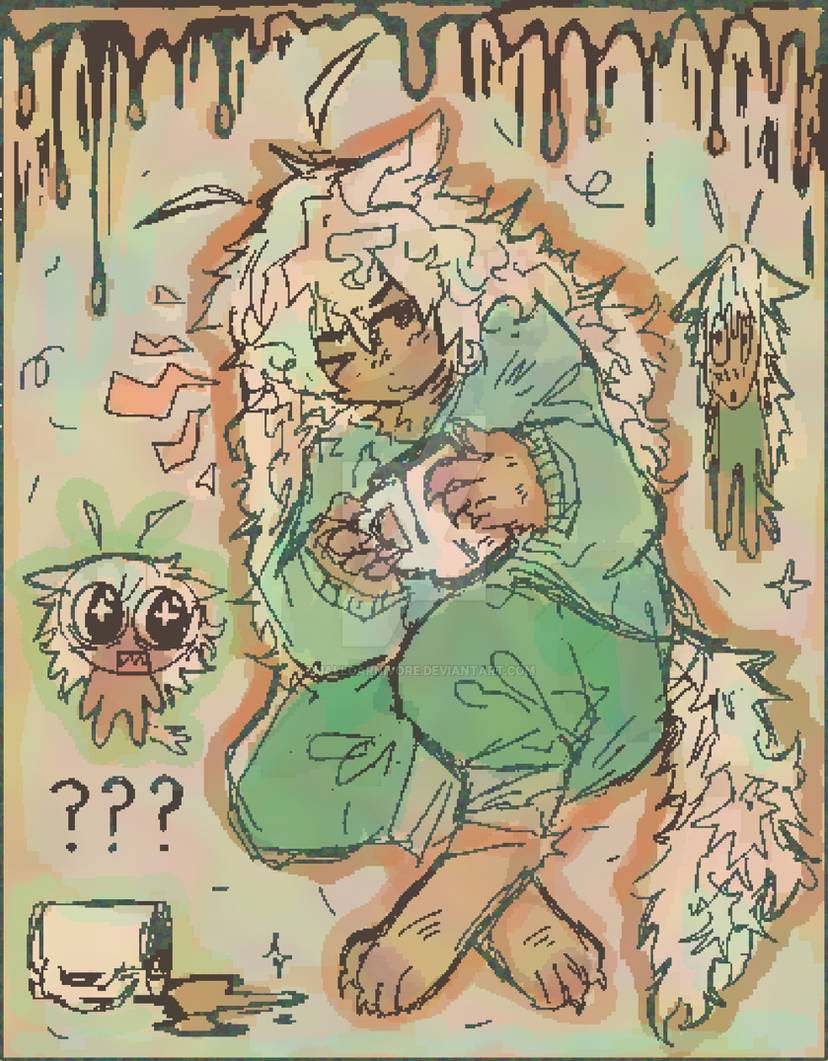

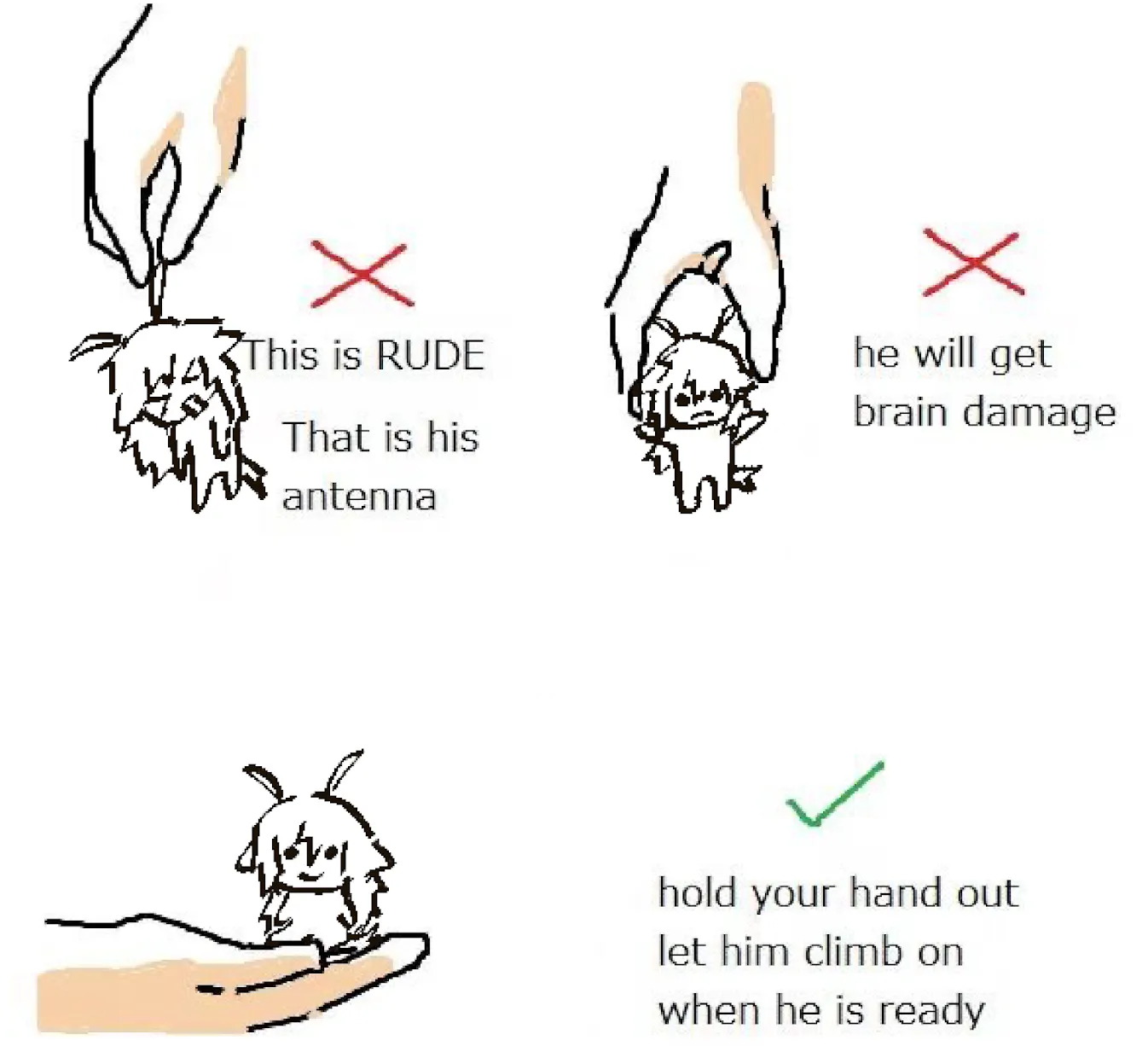

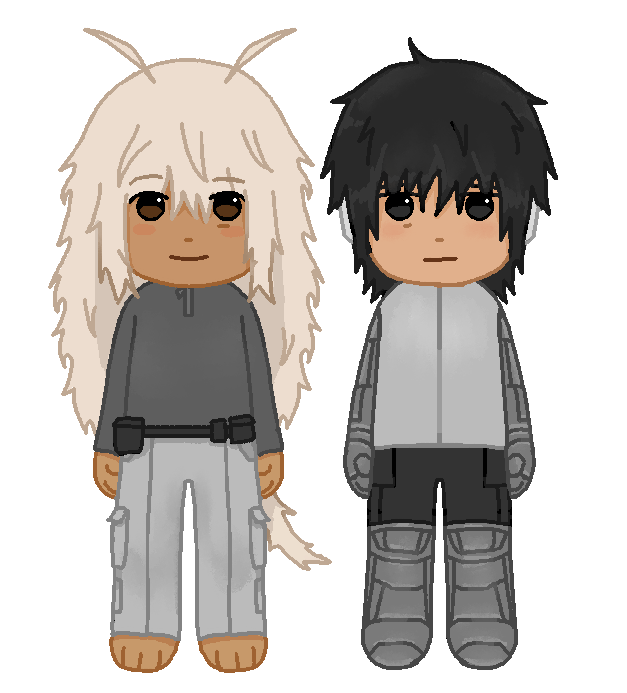

Almost all art I've made for this project :)

CENTRAL TRADE AUTHORITY

GENERAL INFO

Type: Pseudo-governmental entity

Status: Active, but declining

Region: Spans 7 major systems (Core Sector, Outer Colonies/Rings)

Founded: Cycle Year 0

Affiliation: Self-governing, non-traditional state entity

Function: Maintain trade routes, utilities, station governance, and itself

1. Overview

The Central Trade Authority is a pseudo-governmental and highly bureaucratic organization that grew out of a postwar era from a demand for order and no stable governments after the war ended. The CTA spans seven major systems.

It was originally intended as a temporary solution to dysregulation and fragile systems and stuck around because no other powers were as organized or powerful as they were/are.

Their current goal is to cling on to power as long as possible, but its authority now relies more on bureaucratic habit and paperweight regulation than genuine control.

Most citizens live in class-segmented strata based on access and identification codes. High-status individuals tend to be Registered Workers, often with full permissions to move, contract, and report income.

“The CTA still exists if it’s decaying, through inertia. It is too big to fail all at once—like a machine still running because no one has shut it off. Systems auto-renew, payments cycle through shell companies, outposts operate independently. Nobody’s really steering the ship anymore, it’s just drifting.”

2. History

The CTA formed in 0 CY as a post-war consolidation of trade and survival functions. It was not founded by a single person but by many quartermasters, relay engineers, archivists, and many more. They recognized that no faction could feed its people alone and that the only lasting winning move after the war was standardization.

The CTA was formed as a way to manage resources and stabilize the world after a major interstellar war involving resources and production disputes between nations. It eventually amassed enough power and situated itself as the general authority but distanced itself from the concept of becoming a government and an empire because of its origins and goals socially/culturally.

The ID and Market Registry system was introduced as a way to make trade and work contracts easier and more widely applicable as a strategy. The Market Registry allowed employers to check past work and experience of potential workers and allow workers to verify if their employers were credible and trustworthy. The introduction of credits and a standardized currency eliminated the struggle of pay transactions and salary conversion. They are easily tracked in the Market Registry and transactions can be monitored closely.

Their charter fixed time, currency, and contract law. The first decade was effectively triage post-war. Chain routes were mapped, rationing was normalized, and sector councils were appointed where elections would have caused power struggles. Stability came from predictable movement. Trains arrived, terminals synced, prices stayed the same, and people stopped starving.

From 10 to 40 CY the Authority hardened into a machine that could think across seven systems. The Market Registry replaced faction registries. The first Core archival building opened with air-gapped backups and paper trails, a (paranoid) bunker against sabotage. The High Directorate stabilized as a committee of committees. Hubworlds grew into permanent nodes, each with a sector committee that could interpret policy without breaking it. These years felt slow but decisive. The war had made everyone tired of improvisation.

From 40 to 100 CY the CTA became culturally dominant. Children grew up never knowing multiple currencies or drifting calendars. Work traveled on contracts rather than rumors. Chain routes gained redundancy, so a broken relay no longer meant famine and panic down the line. Fringe settlements traded predictability for access. Resistance existed, but it was local, brief, and more about dignity than revolution. The Authority’s promise was simple: no surprises.

From 100 to 180 CY internal reforms professionalized everything. Training academies replaced on-the-job improvisation. The Security Enforcement Arm grew from escorts to a full service that guarded routes, audited terminals, and broke forgery rings. The Authority did not declare itself a government because it did not need to. It governed the movement of food, energy, and contracts. That made it sovereign in effect. It called itself an authority to avoid the political obligations a government would claim and fail to meet.

From 180 to 260 CY expansion slowed and maintenance took center stage. The CTA redirected budgets to filtration, habitat upkeep, and agricultural redundancy. Peace in this context meant schedules that did not slip. People adapted by shrinking their ambitions to fit within predictable lanes. Most citizens did not miss voting on distant policy. They wanted clean water, grain shipments on time, and a station that did not vent atmosphere without warning.

From 260 to 320 CY competitors failed to appear because the conditions that create rivals were removed. Chain routes denied alternate currencies the oxygen they needed. Black markets remained but never scaled. Independent polities survived only by specializing in niches under CTA permits. The Authority’s dominance was not theatrical; it was the quiet weight of routine piled into a mountain.

From 320 CY to the present the CTA’s pseudo-governmental nature hardened further. It regulates identity, work, and movement but avoids the symbolism of statehood. Permits and timetables invite compliance. The CTA evolved by refusing grand narratives. It simply promised that if you stayed in the system, you would eat, your air would circulate, and your children would learn a trade. That promise remains the foundation of its legitimacy.

A timeline in CY:

- 0 CY founding and adoption of time and currency.

- 5–15 CY Market Registry and basic chain routes.

- 20–40 CY sector committees standardized and Core Archives completed.

- 60–100 CY chain route redundancy and hubworld entrenchment.

- 120–160 CY SEA professionalized and registry-integrated enforcement.

- 180–260 CY maintenance first policy.

- 300+ CY stabilization culture becomes the default memory.

3. Governance and Structure

High Directorate

At the top is the High Directorate, composed of 9 rotating delegates chosen from Sectoral Oversight Boards. Each director manages a core portfolio for a sector of oversight:

- Transit & Borders

- Energy & Resource Flow

- Infrastructure & Settlements

- Legal & Civil Order

- Security & Surveillance

- Agriculture & Production

- Data Management

- Cultural Regulation

- Emergency Response

A unanimous vote of at least six members is required for emergency acts. No single person holds total authority. Instead, decisions are issued via encrypted releases, signed and timestamped, and forwarded to Sector Heads.

Sector Committees/Oversight Boards

Manage broader operations. These are the sectors of oversight that the High Directorate manages.

Other Sectors

- Systems Maintenance Divisions: Utilities & infrastructure upkeep

- Security Enforcement Arm (SEA): Law enforcement, border control

- Contract Labor Registry (CLR): Tracks itinerant labor

- Programs Division: Projects like SEVRA

- Market Registry: Six-tier citizen status system controlling mobility and access

Authority flows downward from the High Directorate through defined administrative layers. Most power is centralized in the Core.

There is a strong separation between public-facing communication and actual decision-makers. Directorate remains insulated and largely faceless.

All major procedural updates, reversions, or directives are delivered via chain broadcasts, secured terminal updates, and other approved channels.

In outer colonies, station administrators and task authorities act independently, as long as they file reports. Most real control comes from resource distribution.

A task authority is a finite delegation of power attached to a specific job. It unlocks the ability to requisition parts, pause a line, override a minor lockout, or sign off on a repair within a narrow scope. Task authorities are encoded in contracts and time-limited.

They are audited after completion and collapse back into the registry when no longer needed.

4. Culture & Key Traits

The identification system used by the CTA (called the Market Registry) assigns every citizen a six-tier status: ID-class, labor-code, mobility rating, medical clearance, registry date, and access tier. Owning an illegal blank ID can result in conscription or re-education. Travel requires work permits or Authority carrier clearance. ID cards are essential to everyday life.

The dominant economy is credit-stamped barter, trade, or smaller-scale sale. The CTA supports spaceports, trade lanes, mining stations, bio-agriculture domes, temp camps, and recycling or repurposing industries.

Travel

Travel and relocation are tied directly to occupational clearance. If a worker’s assigned duties require movement—such as couriers, messengers, traveling medics, or off-site inspectors—they are either issued a certified transport permit or assigned a small registered vessel. Most travelers are temporary workers. Very few are granted housing or residency. In contrast, station-based laborers like agricultural workers, repair technicians, or hydroponics staff typically operate within a fixed radius and rely on local public transport, such as light rail shuttles or suspended monorail cars that move between work zones and communal housing.

People travel when work requires it and rarely for leisure. Chain route movement is a privilege tied to permits and contracts.

Most people prefer to stay where they are because it preserves community, and because relocation demands proof that the new post needs them more than the old one did. There is pride in stability. Movement happens, but the culture treats unnecessary travel as noise.

Celebration & Religious Beliefs

Despite official discouragement, there are still seasonal feasts, naming days, and festivals.

Earth survives in memory as a distant origin rather than a home. It is culturally relevant as a symbol in archives, songs, and images of coasts and fields that most citizens have never seen. There are caretakers and research enclaves, but large-scale habitation is minimal. The planet is allowed to cycle without heavy settlement because replicating a world’s ecology is a task the CTA would not claim to manage. People honor it by keeping a record rather than by returning to live.

Some carry tokens like small dirt capsules or symbolic beads thought to bring balance.

Superstitions and traditions include:

- “Never patch on a reset schedule.” It’s unlucky to repair something bigger during a sector’s system reboot window.

- “Three-knock salute.” Done on docking doors for luck. This comes from an older preventative behavior to check if they were properly sealed before opening. Related to “knock on wood” superstition!

- Scrap tokens: Found machine parts given as thanks, exchanged among close crews. Many people find this to be humorous depending on the type of scrap, and the behavior is not common outside of Fringe areas. Basically, a silly gift giving practice.

- Some stations decorate ducts with soot chalk during cold weeks as a bonding activity with children.

These beliefs are tolerated unless they interfere with labor.

CTA-Sponsored Art

The CTA funds art through sector culture budgets tied to stabilization metrics. When a sector meets agricultural and economic quotas, a small percentage is released for cultural commissions.

The favored forms are durable public works such as large reliefs in transit halls, corridor murals in stations, and archival photography that documents infrastructure milestones.

The venues are markets, station centers, hubworld plazas, and the anterooms of sector committees. Commissions primarily go to registered collectives and guilds first rather than individuals so contracts and maintenance can be tracked. People can own small works if they are registered and non-speculative, such as a hand-carved panel or a print from an approved press. Owning art is more common in the Core.

There are artists who work directly for the CTA, but they are not independent in the way artists might have been in older states. They are hired under cultural commissions, usually tied to sector committees or the CTA’s goal of longevity. Their contracts look more like engineering jobs than artistic careers, with deadlines, material allocations, and maintenance requirements. Their job is to produce standardized civic art such as murals of chain routes, reliefs of agricultural harvests, posters that show workers smiling at terminals, and educational illustrations for schools and registries.

For propaganda, the CTA prefers subtle reinforcement over overt slogans. The art is designed to make daily life appear orderly, reliable, and worth preserving. Posters might depict “model workers” standing proudly next to grain silos. Murals often show chain routes as shining lines across the stars, with crews maintaining them in harmony and SEA workers protecting them. Artifacts of disorder, chaos, hunger, or decay are rarely shown. Instead, propaganda emphasizes predictability.

Art matters to the CTA because it broadcasts continuity. A mural that depicts a chain route being repaired is effectively propaganda with a gentle face. It turns logistics into identity and teaches a population to see order as culture.

Clothing

Most everyday clothing is made from a mix of station-grown plant fibers (textile specific flora, reprocessed flax/grains), cultivated animal products (wool, low-shedding fur), and tough, patchable synthetics. In the Core, polished synthetic blends and high quality fibers dominate, but further out, layered insulation and woven composites are common. Clothing is expected to last and be reworn—many pieces are modular or reversible. Damage is repaired visibly with thread or scrap patches, sometimes used to track travel history or station origin. It’s a sign of how much you have done.

Basic Uniforms

- Reinforced collars, breathable fiber-blends

- Utility belts with ID tags and key modules

- Sector-specific patches: color-coded and barcoded

- Regulation boots, magnetized soles optional

Higher-Level Wear

- Director-level personnel wear minimalist folded cloaks over uniforms

- All insignia are small and unobtrusive. The CTA values modesty, not spectacle

Most uniforms are slate gray, forest green, or rust red, depending on the area and level.

Resistance

Rebellion itself is rare, but organized resistance does exist, especially among those displaced by defunded programs. These groups are nonviolent, operating in information blackouts, focused on leaking data, reconnecting families, or protecting outliers. Most of these are restricted by the same bureaucratic limitations as everyone else: relocation requires paperwork, signal control is tight, and surveillance layers are deeply embedded. This is why rebellion is so localized and tightly controlled, since this specific weakness plays to the strengths of the CTA’s power.

People rebel because the system is heavy. The surveillance, the certainty, and the endless permits feel like a lid. Some want more room to invent or to trade outside fixed prices. Others want recognition for communities that do not fit the standard. Rebellion takes the form of signal piracy, black-market identity swaps, labor slowdowns, and occasionally the sabotage of a relay that will force a negotiation. Most people are not actively upset. They are resigned. They criticize in private and work in public. The system survives because it delivers food and air and because the alternatives look like the war.

Death

Bodies aren’t normally buried. Instead, they are quickly cremated and their ashes are compressed into stones. Medical death is logged through the Market Registry.

Unclaimed bodies are repurposed into nutrient or thermal reclamation units, depending on the state of the body.

If they are in good condition and may be identified in the future, still photographs are taken and the body is processed normally and stored in a facility for unclaimed persons until someone claims them. There is a waiting period of several cycles before the body undergoes the same treatment as unidentifiable bodies.

Memorial walls in stations list names and contract spans. Families and crews hold small gatherings where work stories are told because work is what the person did and the language people share.

Children are told that death is a completed cycle and that records keep memory safe. Dying people put their contracts in order, archive messages, and select whether their tools or keepsakes pass to a trainee. The attitude is accepting rather than mystical.

Education

Basic literacy and math are mandatory by CTA law. Most children attend station-based communal schools until age 9, then move into either apprenticeship tracks or continue in academic cores (rare). Vocational training is handled by union tutors, station elders, or family lines.

There is quite a lot of indoctrination. Lessons often begin with CTA history and end with procedure. Even arithmetic problems use trade examples. Children grow up seeing the Authority not as optional but as the natural shape of the universe.

Old tech manuals, field books, and digests circulate heavily. There’s a culture of knowledge preservation through hand-copying and analog archives. Programs exist to restore damaged texts.

Education is standardized to set a floor. Children learn reading, terminal fluency, basic numeracy, maintenance safety, and the history of the CTA in simple terms. Schooling is not made to be thrilling, but it is steady and predictable.

The highest level is sector academy certification in a specialty such as filtration, relay networks, hydroponics, or logistics. Education gets you priority in contracts and better housing allocations.

Apprenticeships pair a trainee with a certified worker for set hours and milestones. Vocational training is hands-on in live systems with strict supervision.

Failed apprenticeships are permanently stamped in the registry, though marked as “incomplete” rather than failure. Still, this record limits future opportunities, making it hard to shift careers.

The most prized subjects are those that keep the lattice up: agriculture, filtration, power, relay maintenance.

The Authority standardizes because a system is only as strong as the weakest training run.

Childcare/Childhood

Kids are raised communally on most stations, especially in fringe zones. Parents may be part of their lives, but early childcare is rotated. Communal meals, station-wide birthdays, and holiday events build identity. Children wear ID tags embedded in clothes and are assigned a primary caretaker.

If a child is born outside the registry, they are given a temporary field tag and must be formally registered within 3 cycles of birth to receive official rations and education.

Children raised on CTA-registered stations are assigned “Baseline Labor Track” tags at age 8. These determine future housing eligibility, job offers, and educational tier access.

Labor classes can shift up (slowly) through exceptional merit or strategic transfers—but very few reach Core eligibility without direct sponsorship or fabricated documentation.

Toys are usually made from cast metal, molded scrap plastic, or carved waste-wood (a hardened agricultural byproduct). Most children own small figures—often shaped like creatures, machines, or folk figures. These are passed down, repainted, or bartered. Some toys come from rotating trade routes and include puzzle-cubes, slide disks, or noise tiles.

There are no mass-market toys in the current time period; everything is handmade, swapped, or improvised. They used to be produced consistently for schools, but now that the stock has leveled out they don’t produce any more.

Children are treated as learners and future workers, but not as projects to be accelerated. Typical childhoods are remembered as safe, structured, and a little dull.

Hobbies include simple crafts, station games in narrow corridors, and music made with communal instruments.

Clothing is unisex and practical, sized by growth class with colored stitches that mark care group rather than gender.

Older children tend to guide younger ones, especially in terminals and safety drills, because competence is a form of kindness in this culture.

Pets

Domesticated animals (specifically pets) aren’t common but do exist. Cats are favored for their low maintenance and adaptable personalities—shared pets in communities, often “belonging” to no one but fed by everyone, are common and especially helpful in agricultural settlements as they take care of any creatures made for maintenance that might escape. In smaller family units, children might keep agricultural beetles or lizards for a cycle or two. Pets other than cats are seen as soothing but impractical; their presence usually depends on access to food, space, and breathable zones.

5. Population & Demographics

The vast majority of the registered population is baseline human. Across CTA space, humanoid variation exists, but extreme divergence is rare due to shared environmental pressures, interspecies compatibility laws, and social standardization efforts.

Humans have adapted more in culture than in body, though medical and biomechanical aids are common. Average life expectancy is higher than pre-war in stable zones because filtration, vaccination, and accident control are consistent.

Some lineages carry legal modifications for specific work environments. The baseline remains recognizably human.

Most citizens live in class-segmented strata based on access and identification codes. High-status individuals tend to be Registered Workers, often with full permissions to move, contract, and report income.

Most workers carry a patchkit (for clothing), a multitool (blade, wrench, heat-sealer), and a Market Registry ID card. Some also carry compact respirators or filters, depending on the sector. These tools are so common that not carrying them marks you as a visitor or outsider.

Relationships form through necessity, proximity, or shared contracts. Most bonds start from cohabitation or years-long work placement overlaps. Marriage is mostly symbolic unless registered, which grants you permission to share housing legally and merges your files.

Most citizens are literate, as all official processes—rations, jobs, permissions—require competency with CTA terminals. A majority live in dense housing blocks or mobile freight colonies. Many take jobs like:

- Systems maintenance

- Cargo relay

- Basic medical or recycling labor

- Station agriculture

- Contract navigation or inspection

6. Infrastructure

Terminals

A terminal is the standardized interface device through which all CTA communications, transactions, and authorizations are carried out. All terminals can use the standard terminal code.

They serve as the primary line of communication between individual workers, managers, and the wider systems of authority. Terminals are highly regulated pieces of equipment, manufactured to uniform specifications to ensure compatibility across all CTA jurisdictions.

Medical Care

Medical care is standardized, decentralized, and paperwork-heavy. On Core stations, it is streamlined and advanced program-assisted diagnostics, micro-surgery, limited appendage regrowth. Further out, there are mobile clinics, licensed med-techs, and CTA-issued field guides on care.

Mobile clinics can ride chain routes and set up in hours, bringing lab basics, imaging, and stabilization. A med-tech must pass modules in triage, sterilization, device safety, and terminal logging.

Sophisticated technologies include organ scaffolding, nerve-bridge prosthetics, and slow-print tissue patches for superficial regrowth. Appendage regrowth is limited to small structures using printed matrices and growth factors; full limb regrowth still relies on advanced prosthetics. Risk is assessed by triage protocols that weigh survival, resource cost, and contagion risk.

Med-kits are common. A standard med-kit contains wound sealant, broad-spectrum antiseptic, analgesics in measured tabs, splints, adhesive wraps, a portable scanner for vitals, airway inserts, burn gel, and a compact auto-injector for allergic or shock events.

Medical history is stored on terminals, linked to ID cards. Local clinics may keep paper backups, but most trust the Core Archive to maintain them.

Most zones have at the very least one or two registered caretakers trained in basic triage and diagnostics. Prescriptions are tracked, and care is rationed by risk index and not wealth. The typical experience with healthcare is simple and straightforward, often with a local clinic or doctor.

Prosthetics for the average citizen:

- Modular prosthetics exist, though rarely super fine-tuned.

- CTA health grants provide baseline arms/legs durable (unless more is required or requested).

- Customization is done by trade guilds, underground technicians, or family units.

- Maintenance is scheduled a bit like engine repairs.

Disability is seen as a logistical adjustment, not a limitation. Most stations support ramps, signal tools, adjustable uniforms, and assisted work pair matching. Prosthetics, translators, and sensory tools are repaired alongside other vital equipment. Community-based care networks provide continuity. No official stigma exists in documentation; accommodations are integrated into worker roles and reviewed at contract renewals.

Waste

Nothing is thrown away in CTA systems unless it absolutely must be. Organic waste (especially sewage) is chemically sterilized (excluding beneficial decomposers) and converted into high-efficiency agricultural substrate. Trash is sorted…metal to be smelted, cloth for patchkits, composites pulped into insulation or filler. Refuse is cycled into what stations call “gray loop” systems, where materials are tracked from use to reuse. Disposal protocols are maintained as part of every work rotation.

Jobs range from intake operators and sorter techs to gray loop engineers and reclamation chemists. Gray loop systems are mid-grade recirculation lines that turn mixed low-risk waste into usable feedstock for non-critical products such as packaging, spacer panels, and conduit sleeves. Dangerous materials are isolated in shielded containers, logged, and neutralized or vitrified depending on type.

Reclamation rates are high in the Core and hubworlds because the network is dense. In periphery stations the rate is lower but still significant. Metals, plastics, fabrics, and water are the most successfully recovered. The design goal is to make export growth possible without importing raw materials no one wants to pay to ship.

What are patchkits?

A patchkit is the textile equivalent of a med-kit. It contains adhesive fiber patches, heat-activated seam tape, repair needles, thread spools matched to standard uniforms, small rivets, and a compact seal tool. It mends clothing, soft gear, and some flexible gaskets. Workers carry it because a torn sleeve is a safety risk when fabric fouls a machine.

One overlooked element of waste is cultural salvage. When stations decommission clothing, posters, or consumer goods, some are archived rather than recycled to provide cultural continuity. Archivists argue that not every scrap should be pulped, so a subset is logged and stored in Core vaults.

Another piece is wreck reclamation, where crews in black zones strip wrecks and scrap for unofficial resale. The CTA technically bans this, but it is tolerated when the materials eventually cycle back into official markets.

Water

Water is drawn from one of three main sources:

- Local melt (on icy moons or asteroids, or surface water if available)

- Condensed vapor harvesting (standard on orbitals)

- Shipped ice blocks (expensive, rare)

- Synthesized from local materials or recycled

Water is stored in central tanks, filtered continuously, and moved through low-pressure loop lines. Some stations add trace minerals for health; others let it run slightly stale. Outpost dwellers sometimes have personal filters or boil it directly from condensed runoff.

Artificial Climates

Most stations and dome settlements regulate “weather” via pressure, humidity, and heat cycling systems. There are no real seasons, but many use light-tinting adjustments to simulate morning and evening to reduce circadian dissonance. Temperature and calibration varies by sector:

- Agricultural zones use more specialized artificial control systems based on crops or agricultural practices.

- Freight and docking areas remain colder and dry to preserve material.

- Living quarters aim for comfort.

Static buildup, drip condensation, and sudden air shifts are signs of mismanagement and are easy to spot, though rare if regularly worked with and routinely up-kept.

Illegal & Obsolete Technology

Illegal technologies are generally those that bypass CTA oversight, compromise chain route security, or undermine registry control.

Unregistered signal repeaters that let ships spoof their chain slot are illegal because they can disrupt traffic timing and mask smuggling practices. Proprietary encryption layers over standard terminal code are illegal when they prevent audits, since the Authority must be able to verify all transactions.

Autonomous weapons with target selection outside approved parameters are illegal because they can escalate disputes without human accountability.

Memory extraction rigs that copy terminal credentials from a worker are illegal since identity integrity is the foundation of the Market Registry, and extraction rigs that copy the secure information of a ship are also illegal because of the nature of transportation regulations.

Biotech that alters registry biometrics without a clinic license is illegal because it breaks the link between a person and their contract history.

The common trait is that each item severs a control point the CTA considers essential to stability.

Obsolete technologies linger in warehouses and scrap yards but are rarely used because the standardized system has moved on.

Early relay towers that required manual synchronization became obsolete by 40 CY when self-correcting relays reduced drift. Paper scrip and wax-sealed permits disappeared by 15 CY once terminal-linked ID cards could store contract data and time codes. First-generation cargo trackers with single-channel beacons faded out by 30 CY because they could be spoofed too easily.

None of these are unusable, but they are dated. They persist in black zones where replacement parts are cannibalized and compatibility layers keep them limping along.

Obsolete equipment is tagged with orange registry stickers that show its replacement order. People still use them until the order is fulfilled, but the tag is a constant reminder. In some stations, workers decorate old tech with drawings or inscriptions, treating them like elder tools on their last cycle.

Accidents involving old equipment being reused too long usually become case studies in training manuals if they are big enough problems. Each is stripped of names and turned into a procedural lesson: “Case 94: improper valve reuse led to loss of two contractors.” Families of victims often resent this depersonalization, but it reinforces the CTA’s attitude that personal lives are secondary to systemic efficiency.

The CTA does not ban them unless they cause risk, it simply refuses to support them, which makes them die on their own.

THE HIGH DIRECTORATE

GENERAL INFO

Type: Central policy-making body

Composition: 9 rotating anonymous delegates

Location: Primarily Core-based

Authority: Emergency acts require 6/9 unanimous vote

1. General Description

The High Directorate is composed of 9 rotating delegates chosen from Sectoral Oversight Boards. They are the central policy-makers and manage the most for the CTA. Each director manages a core portfolio for a sector of oversight. They are as follows:

- Transit & Borders

- Energy & Resource Flow

- Infrastructure & Settlements

- Legal & Civil Order

- Security & Surveillance

- Agriculture & Production

- Data Management

- Cultural Regulation

- Emergency Response

A unanimous vote of at least six members is required for emergency acts. No single person holds total authority. Instead, decisions are issued via encrypted releases, signed and timestamped, and forwarded to Sector Heads.

The High Directorate operates under extreme secrecy—not only are members never identified publicly, they are also kept anonymous from each other. Roles rotate in fixed intervals, and identities are cycled through secured, air-gapped relay drops. This prevents consolidation of power, limits infighting, and shields the Directorate from retaliation. Should a director die or disappear, a silent succession protocol is engaged, and no notification is ever broadcast beyond the inner circle. They are mostly based in the Core.

This structure evolved out of post-war necessity when the CTA transitioned from a trade coordination bureau into a massive control body. The only major shift in structure was this expansion; otherwise, the Directorate has remained rigid, faceless, and functionally immutable.

2. History

The High Directorate was conceived alongside the CTA, and has survived with minimal change since the founding. It originated as a variant on a board of directors, modified for postwar stability and safety. This is why they operate in such extreme secrecy, to the point where they do not even personally know each other.

3. Correspondence Examples

EXCERPT — INTERNAL CTA CORRESPONDENCE

CLASS: Internal Memorandum

ACCESS LEVEL: DIRECTORATE ASSEMBLY ONLY

ENCRYPTION: SIG:AE-13|H-Redundant Backflow Checksum Enabled

RE: Directive Proposal — Sectoral Compost Reallocation (D-4893B)

FROM: Dir. ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ (Infrastructure & Settlements)

TO: Full Assembly | Logged: Core Date 781.44.03

CC: Sectoral Governors of Hydrone Belt, Eastern Interior Ring

Esteemed colleagues,

I raise this proposal under Article VI of the Interstation Sustainability Accord. Current compost recapture rates in the outer hydric loop of Sector 5-E remain below the 35% sustainability threshold. Based on submitted reports from Node 9A (Port Revach) and Node 11C (Sisto Cradle), both stations are rejecting standardized composting bins due to space limitations and outdated chute-routing systems.

I propose emergency redistribution of excess compostable bio-waste to the satellite domes of the Inner Crescent, where reactor-grade composting systems are already in place. This bypasses the need for short-term capital upgrades in the struggling outer ring. It will require one-time overrides of regional autonomy clauses in settlement waste cycles (Article V, Section 2).

Resistance is expected from the Agricultural Syndicate, as their members rely on “closed-loop” growing systems and consider off-station biomass input a contamination risk. However, projected nutrient yields on recipient domes will increase 12–18% in the short term.

Requesting emergency assembly vote.

Dir. ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇

Infrastructure & Settlements, CTA Core

RESPONSE FRAGMENT (Logged 7h Later)

FROM: Dir. ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ (Security & Surveillance)

“Be advised: the risk isn’t contamination—it’s perception. Outer stations are already under the impression that we dump surplus or unregulated materials without notice. Redistribution without full transparency could trigger retaliation, especially in places like Revach with strong pseudo-union blocs. If we push this, we’ll need a general terminal messaging package and two clean audits to cover it. I’ll authorize temporary overrides if your sector bears fallout with public relations should you decide not to fully detail the process.”

VOTE OUTCOME:

Proposal D-4893B passed with a 6/9 Assembly majority

Conditions:

- Full traceability audit

- Limited press disclosure

- 6-cycle review period.

SECTOR COMMITTEES

GENERAL INFO

Type: Localized administrative extensions

Scope: Assigned zones (often planetary systems)

Authority: Logistical implementation, limited independence

Sector committees act as localized extensions of the Directorate, managing day-to-day operations within assigned zones. Each committee is composed of administrators and managers drawn from relevant divisions. A sector can encompass entire planetary systems, with boundaries drawn along logistical rather than geographic lines.

Committees have little independent authority. Their role is logistical, not political, ensuring uniform application of policy.

Members are appointed by higher Authority approval, often selected from proven administrative backgrounds.

Sector committees bridge the gap between local administration and the Core. They translate policy into practice.

Their uniqueness lies in their autonomy. While they answer to the Core, they are granted broad discretion to manage their regions, reflecting the CTA’s pragmatic recognition that one size does not fit all.

Their authority is significant yet limited. They manage contracts, permits, and resolve disputes within their sector, but lack the power to modify Core directives.

They are valued as stabilizers. Without them, the Core could not manage the scale of the CTA.

Committees in resource-rich or strategically vital sectors wield disproportionate influence. Others remain minor players.

They can be compared to a mix of provincial governments, colonial administrators, and corporate boards. Like provinces, they manage local populations; like colonial administrators, they answer directly to a distant central authority; like corporate boards, they balance the books of their sector. They are strong within their own territories, but always bound by the Core’s authority.

Sector committees began as ad-hoc governing bodies during the early stabilization years, around 5-10 CY. At the time, the CTA High Directorate could not micromanage every outlying sector, so temporary “sector councils” were formed from a mix of military officers, agricultural overseers, and local administrators. Their early responsibilities were basic, and they were tasked with distributing rations, preventing riots, and enforcing credit use. They were poorly funded, often corrupt with ulterior motives, and sometimes collapsed under local pressure. Still, they provided the first major decentralized experiment in CTA administration.

As stability grew, these councils evolved into permanent sector committees.

By 20 CY, they were standardized into semi-elected, semi-appointed boards with permanent offices in each hubworld. Their responsibilities expanded to include contract verification, chain route oversight, and economic balancing. Unlike their early predecessors, these committees became heavily bureaucratic, employing clerks, inspectors, and auditors who were trained directly by the Core. Their authority widened over time, and they eventually became the most visible form of CTA presence outside the Core itself.

The history of sector committees reflects the CTA’s broader shift from military enforcement to a focus on predictable stability. Originally temporary stopgaps, they became permanent because they solved the Core’s problem of how to govern their more distant populations without sending endless slews of administrators.

Sector committees act as mid-level administrative bodies, handling contracts, disputes, and logistical planning within their territory.

Their responsibilities include:

- Implementing directives from above.

- Reporting local anomalies.

- Coordinating food, energy, and housing supply.

Day-to-day, sector committees operate as a blend of local government, regulatory office, and trade management board. Their routine includes verifying contracts, issuing permits, overseeing agricultural quotas, and adjudicating disputes between contractors. Most of their time is spent processing applications and mediating between local settlements and the Core.

Committee offices are busy with clerks logging trade manifests into terminal systems, while inspectors are dispatched to confirm that reported yields, repairs, or relocations match what’s actually happening. They are also responsible for ensuring stabilization sectors (like agriculture and filtration) receive supplies on time and that chain route checkpoints in their sector stay operational.

A single committee might spend a week approving a new hydroponic facility, while simultaneously reviewing the annual audit of a periphery station and allocating emergency rations to a settlement hit by crop disease.

Disputes between sector committees are not settled by majority vote but by escalation. Each committee files a formal brief through the Sector Registry, and the High Directorate assigns a mediator from the Core. This mediator does not rule based on fairness but on systemic efficiency and which side’s plan aligns more closely with CTA protocol and throughput goals. This has made disputes less about ideology and more about who can argue better within standardized formats.

DAMIR & MAREK

1. About

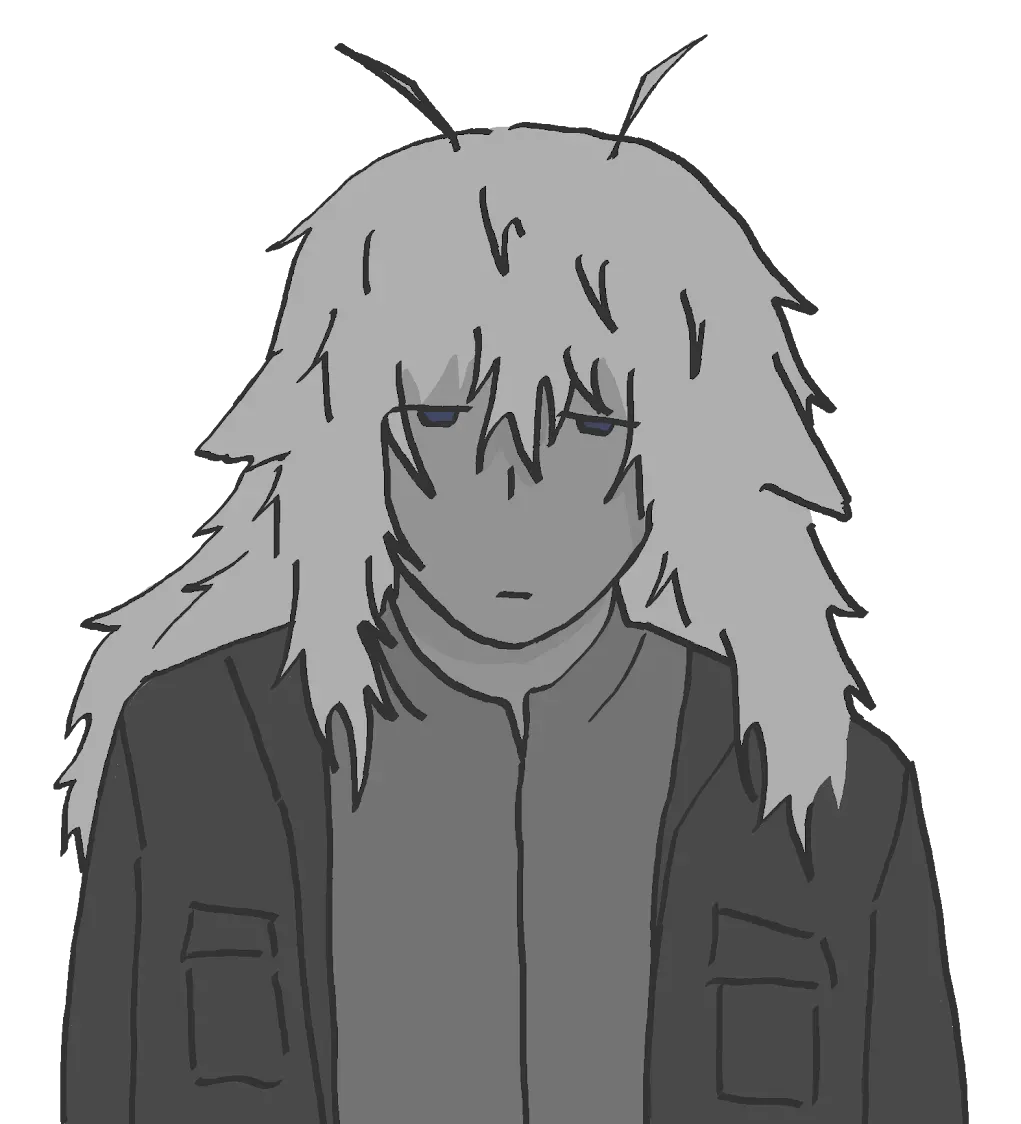

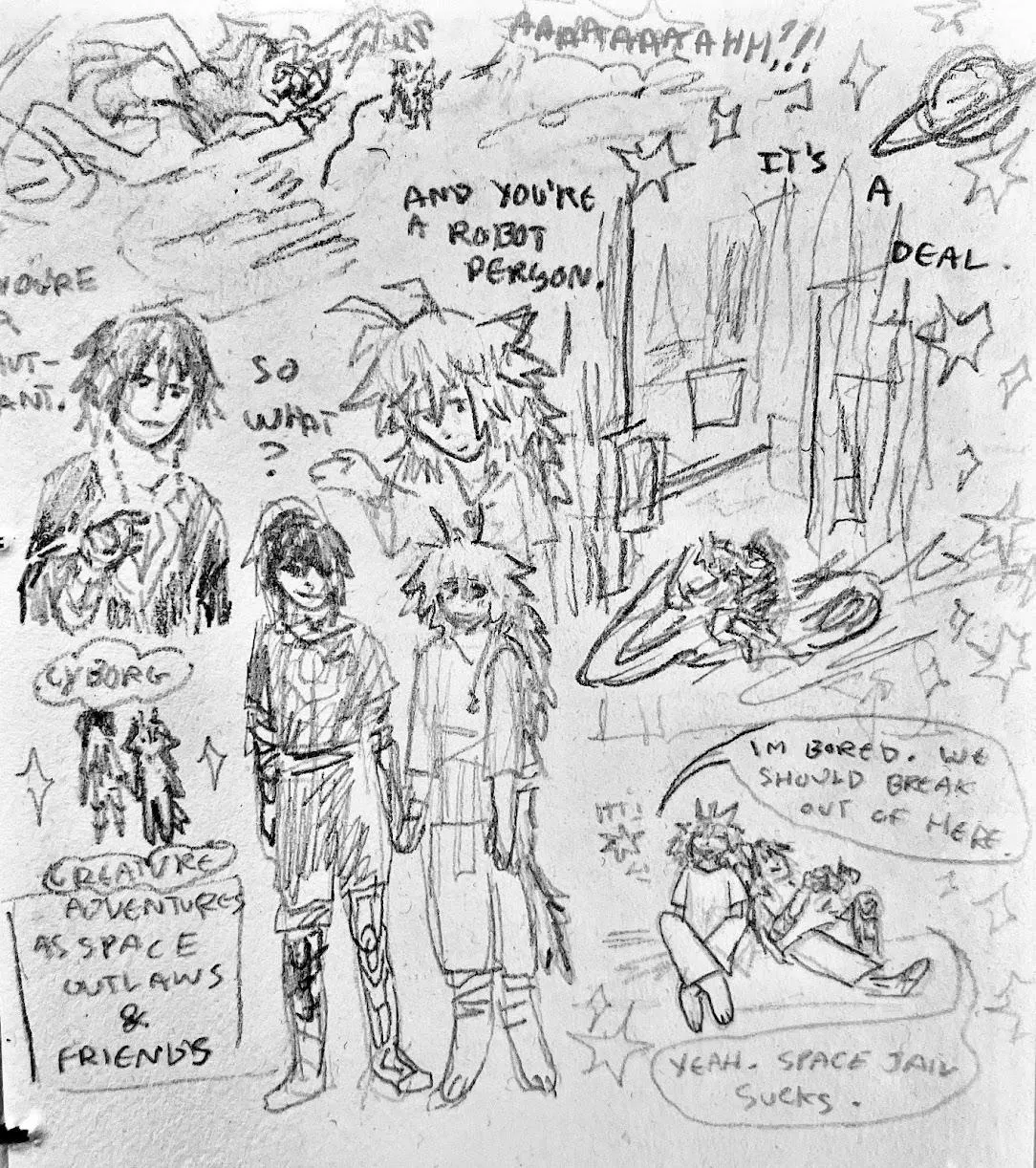

Damir is a visibly altered humanoid, and one of the two main characters. He is consistently seen with Marek, as they are friends and both originate from the SEVRA secret CTA initiative where they were raised.

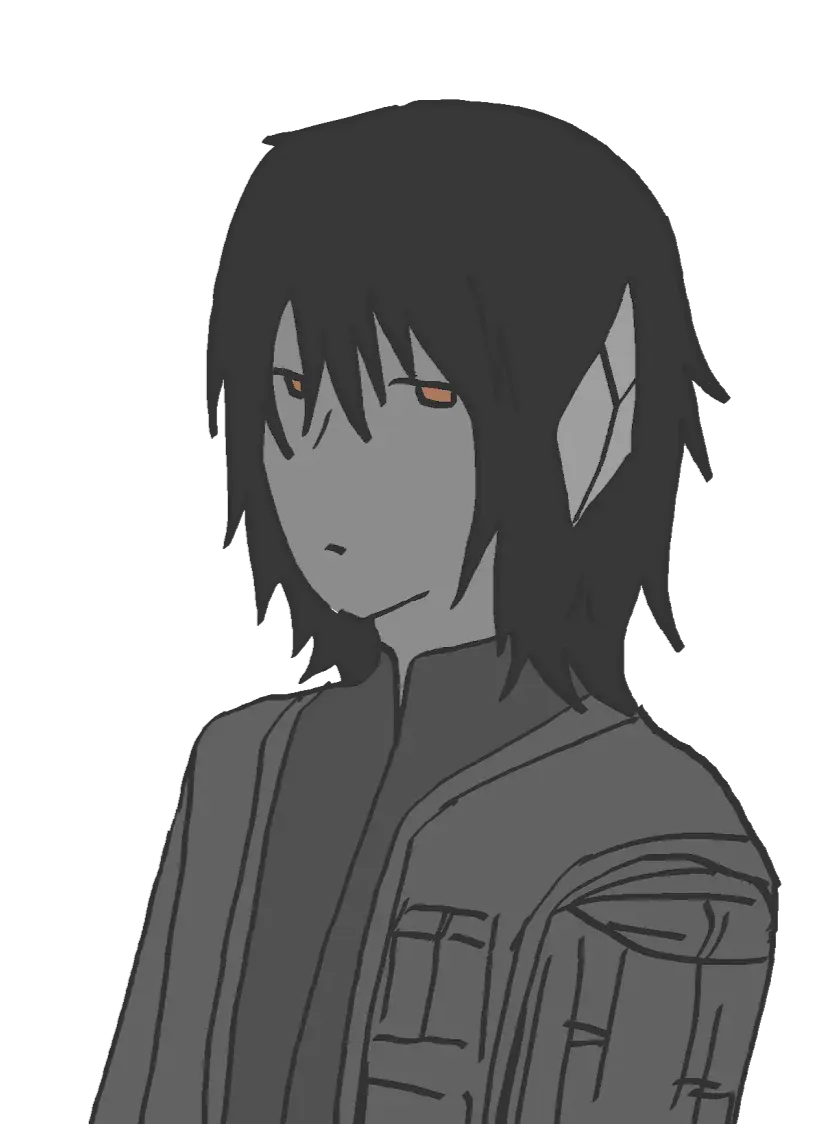

Marek is a visibly altered cyborg, and one of the two main characters. He is consistently seen with Damir, as they are friends and both originate from the SEVRA secret CTA initiative where they were raised.

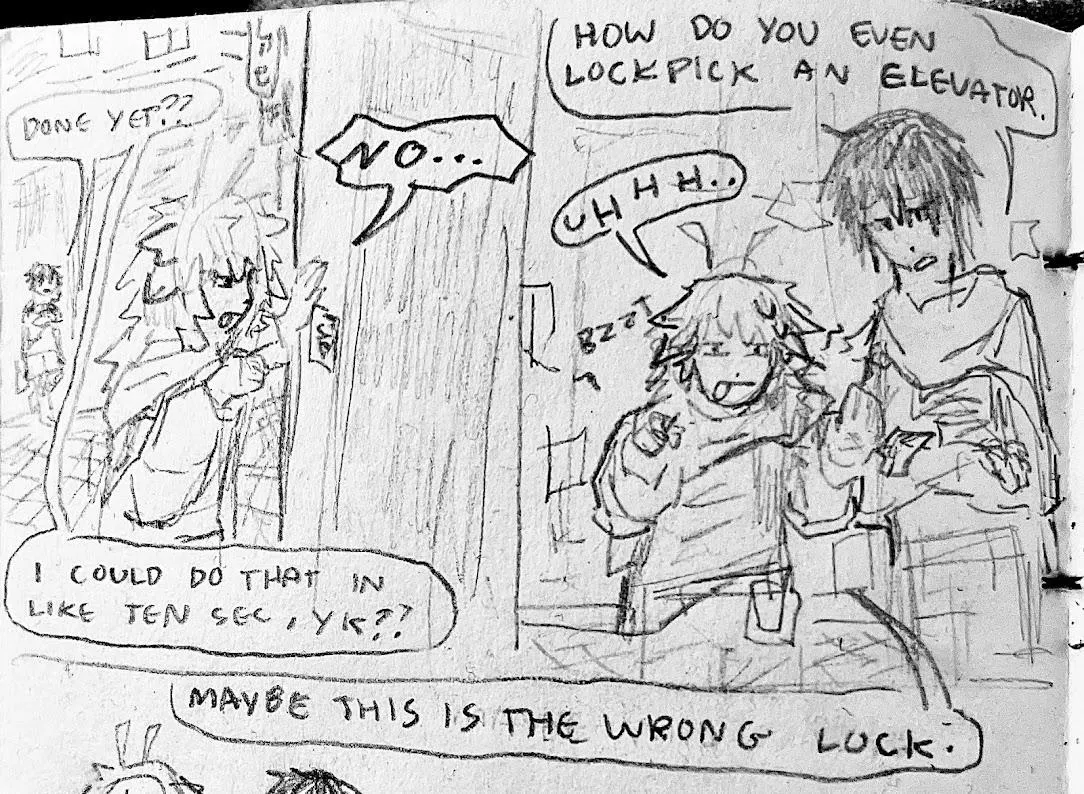

They function as field operatives, taking on assignments requiring both technical knowledge and adaptability.

Their attachment is deep but not pathological. Having been raised in SEVRA’s pair-dependent system, their bond is survival-based, later evolving into authentic loyalty and affection.

Separation is still destabilizing. Both grow anxious and unmoored, struggling to function without the other.

Damir’s technical adaptability pairs with Marek’s logistical precision. One improvises, the other ensures nothing is lost in the process. Their training drilled them to operate as halves of a whole, and that balance remains even now.

They remain together because they choose to, even after SEVRA dissolved. What was once an enforced dependency has evolved into genuine companionship, though neither could easily live without the other.

Their ship, the HAULER-DREV-3349, was acquired after decommission. They claimed it through a mixture of salvage rights, abandoned paperwork, and sheer persistence.

2. Early Life (SEVRA Project)

Both Damir and Marek were raised as a duo in the SEVRA project. They trained as a paired unit, Damir specializing in adaptive tactics, Marek focusing on technical systems. Together, they formed a complete operative. Damir was trained to repair Marek and figure out logistics and construction. Marek was trained to be functional and effective at repair and a variety of tasks (as they both were), focusing on the physical side of their intended work.

Their childhoods are remembered as both cruel and formative. They acknowledge the damage but also see it as inseparable from who they are. For them, regret and acceptance coexist.

They matter because they embody SEVRA’s legacy, proof that the experiment failed in intent but succeeded in shaping lives that persist despite it. Their existence is effectively living history.

3. Personality & Traits

They are outsiders, tolerated but rarely embraced with open arms. Their appearance, training, and bond mark them as unusual. Still, they carve out a life by being reliable in work that others avoid. Neither are baseline, standard humans as they have both been altered but Damir is more recognizably inhuman. Marek is mostly just altered with mechanical additions.

Damir

Damir is composed and competent in public. He handles communication with station managers, registry clerks, and committee officials, often helping to smooth over major hurdles. His humor surfaces only in private with Marek, though he has been known to lightly joke in public and to diffuse situations. Damir tends to plan ahead and maintain appearances, making sure their contracts remain legitimate. They are viewed as functional oddities by locals. Some admire their competence, and others distrust their closeness.

Marek

Marek is quieter in public, less inclined to handle officials, but no less intelligent. He focuses on technical execution, repairs, and logistical details. He is meticulous, sometimes to the point of rigidity, and balances Damir’s outward-facing role with back-end stability. Privately, Marek is just as strange and playful, but he rarely shows this to outsiders.

4. Q&A

How do Damir and Marek communicate on the ship?

Mostly through terminal logs and notes other than speech. Damir tends to speak more freely. Marek writes more often by adding small, dry notations next to system tags.

Where do they get replacement parts for Marek’s body?

Piece by piece. Most parts are scavenged, bartered, or custom-fit from older cargo hauler systems. Sometimes Damir retrofits components from agricultural bots or decommissioned loaders. The replacements are rarely perfect—Marek adjusts his own gait algorithms to account for mismatched torque or outdated feedback coils, and Damir fixes anything he can’t do himself (which is a lot, for SEVRA safety reasons).

How do they avoid drawing attention when docking at stations?

They use pre-written manifests with deliberately boring job codes. Their ship’s ID ping is rerouted through at least two dampener loops, and Damir routinely scrambles any biometric echoes during approach. They never stay more than 40 hours in one port, and they always dock at underused spots—usually ones marked for maintenance or freight spillover.

What do they do in their downtime?

Marek calibrates or rewires whatever isn’t already running. Damir listens to reconstituted audio loops or replays local signal archives for background noise. Sometimes they just sit near the window bubble and don’t talk. Damir occasionally tries to cook, but most of their food is rehydrated or scavenged. They have a few small children’s board games and a stack of cards. Crafts are handy when they have nothing much to do on the ship.

What was their last official job with the SEVRA unit system before going off-registry?

Ventilation flow control retrofit in a dome zone for repair training. Their contract ended early after the station admin was reassigned mid-cycle and no one filed their release logs. After around four days waiting, they were transported back to the main facility.

Why hasn’t the CTA come after them directly?

To be totally honest, they don’t really care that much. The oversight system is overloaded, and their file tags no longer resolve to anything actionable. They appear on outdated registries, flagged as “cleared minor technical contractors.” Without a clear paper trail or post-SEVRA origin stamp, there’s no justification for pursuit unless they trip a current enforcement filter.

What happens if Marek breaks down in a place where they can’t find parts?

He doesn’t. Damir won’t allow it. They carry at least four core components at all times—wiring bundles, a backup arm motor, and two fuser cells. Marek is trained to operate under partial function and has memorized procedures for four degrees of catastrophic failure.

Do they ever try to reach other SEVRA survivors?

No. Not actively.

What does their ship smell like?

Dusty cardboard recycled from agricultural waste, caramelized citrus peels, metal, old fabric, and the faint trace of disinfectant pads. When they’re cooking, it smells like potato and mild spices.

What’s something they’ve never told each other?

Damir knows Marek’s original diagnostic file number. Marek knows that he used it to bypass a terminal system error one time but doesn’t question it.

5. Work

After SEVRA ended, they floated on the edges of legitimacy: odd jobs, hauling, repair, occasional contracts. Their life is patchwork, but it sustains them.

Jobs Taken:

- Water filtration stabilization at asteroid mining camps

- Cooling and humidity regulation for crop domes

- Temporary AC/electrical repair for refugee processing stations

- Transport of sensitive materials, some of which turn out to be illegal (unmarked biowaste, unregistered bots, black market meds in nondescript containers)

Status Now

- Current Goals: Keep HAULER‑DREV-3349 running, clear two backlogged repair contracts, avoid Core audits.

- Recent Jobs: Hydroponic filter swap, chain beacon recalibration, quiet haul of sealed containers.

SEVRA PROJECT

GENERAL INFO

Type: CTA secret initiative

Status: Defunded, discontinued (CTA Internal Order #RD-204A-99)

Founded: Approx. +100 CY

Dissolved: +149 CY (17 CYs ago)

Affiliation: Central Trade Authority (Extended Behavioral Research Authority, Resource Resilience Division)

Purpose: Produce long-term operatives and labor-capable personnel optimized for harsh-zone survival and system redundancy support.

1. General Description

The SEVRA project operated under fragmented CTA jurisdiction, mainly within the Extended Behavioral Research Authority and the Resource Resilience Division. Its goal was to produce long-term operatives and labor-capable personnel optimized for harsh-zone survival and system redundancy support. The population pool was drawn from unregistered or unclaimed juveniles across frontier systems, processed under Experimental Directive 14-E.

SEVRA units were trained for specialized engineering, field logistics, and dangerous missions requiring both technical precision and emotional detachment. They were deployed where the CTA needed absolute reliability. For example: infrastructure repair in hostile zones, resource extraction, and high-risk survey work.

In theory, there was no failsafe. SEVRA relied on conditioning, not mechanical restraints. The pair-bond itself was the failsafe, separating units destabilized them to the point of uselessness.

Due to the classified nature of the initiative, official CTA acknowledgment of SEVRA ceased well before its logistical closure.

The stated reason for closure was:

“Budgetary reallocation following the cessation of critical engagements and a strategic shift away from in-field recovery models. Long-term side effects among test units considered ‘operationally destabilizing.’”

2. Life in the SEVRA Project

Children in SEVRA were treated as resources, not as individuals. They were given food, shelter, medical care and rigorous education, but affection and freedom were absent. The system prioritized function over well-being.

They were allowed to form bonds, but only in pairs. SEVRA’s central experiment was to raise children in inseparable dyads, reinforcing loyalty to one another rather than to Authority. This bond made them effective in the field, but at the cost of their independence.

Separation often caused breakdowns: disorientation, inability to function, or emotional collapse. The system was deliberately designed so units were unusable if split.

SEVRA facilities were enclosed, isolated, and deliberately secretive. They resembled training compounds more than settlements, stripped of non-essentials.

Training emphasized repetition, obedience, and pair-dependence. Children were drilled in efficiency and survival within tightly controlled systems. Units learned tactical operations, technical repair, and systems management. Pairing was critical and skills were distributed so no individual could operate independently.

Funding came directly from reallocated CTA budgets diverted to secret projects. It was significant enough to maintain facilities for decades, but never fully public.

3. Dissolution

Phase One — Funding Stall

Once restructuring swept through the CTA following a multi-sector financial audit, SEVRA’s funding became bureaucratically inaccessible — not explicitly revoked, but rerouted into general systems rehabilitation budgets. Project leads could not formally appeal due to its unregistered nature.

Support functions collapsed in sequence:

- Psychological Support Teams: Unstaffed

- Biometric Supply Chain: Cancelled

- Food/Nutrient Allotment: Switched to minimal shelf rations

- Onsite Medical/Repair Staff: Reassigned to Core Sector medical rotations

This was the unofficial end, but no announcement was ever made. Sites were left in stasis.

Phase Two — Site Abandonment

Facilities were “closed,” but without formal decommissioning. SEVRA test units were not granted reassignment at this point.

Only one CTA department (Internal Systems Audit, Division E) retained access logs to these locations, and those were marked obsolete by the next year’s system update.

Because of the nature of SEVRA, their facilities were neither dismantled nor left dormant. Instead, they were repurposed after abandonment of SEVRA operations for other projects or research. It was not immediate but in phases.

Phase Three — Individual Dispersal

Survivors of the program (including modified units) entered fringe society or were transferred to other programs. Because SEVRA survivors were never officially “born” due to the nature of the program, they do not exist in the Market Registry unless they are registered via official channels and monitored.

SEVRA did not fail.

It became inconvenient.

Inconvenient things get overwritten.

4. After the Project

From a purely practical standpoint, SEVRA collapsed under its own secrecy and inefficiency. While some units proved effective, the cost outweighed the gain. It was exploitative and dehumanizing, stripping individuals of choice. But within the CTA framework at that point in time, ethics often bowed to efficiency and secrecy. It was born out of paranoia and a desire for controlled operatives who could be relied upon to function under extreme secrecy and loyalty.

Survival after the project was possible but difficult. Many struggled to adapt outside the rigid structure, particularly because society had no place for their skillset or bond. Only those who carved out niches for themselves (like Damir and Marek) found lasting stability.

The CTA views SEVRA as a relic of excess and desperation, quietly disavowed but not entirely erased. Official statements frame it as “a necessary but flawed experiment,” a sign of how far they have since progressed.

SECURITY ENFORCEMENT ARM (SEA)

GENERAL INFO

Type: Logistics police and enforcement division

Mandate: Protect chain routes, registry integrity, audits, and infrastructure

Priority: Prevention of disruption as systems failure

1. General Description

The Security Enforcement Arm protects the physical and informational aspects of the CTA. Their mandate covers chain route patrols, audit enforcement, identity fraud suppression, and the protection of registry offices and archives. They are not an army in the old sense. They are a logistics police that treats disruption as a systems failure. Their public face is routine, with checkpoint inspections, slot compliance sweeps, and investigation teams that follow irregular credit patterns through the registry.

Their priority is not the chase but the prevention. They crack down hardest on forged identities, chain slot tampering, off-standard encryption, and sabotage of filtration or agriculture nodes. Those crimes threaten the system, so penalties are steep.

Local detachments report to sector captains, who answer to a directorate integrated with the Finance and Registry divisions. This prevents the classic split between security and administration. Training emphasizes procedure, de-escalation, and machine fluency. Recruits learn how to read relay diagnostics, trace forged signals, and interview workers without halting traffic. Weapons training exists, but the most valuable tools are audit kits and sealers that lock a compromised node back into standard.

SEA personnel are posted along main chain routes and at hubworld gateways. They manage evidence custody for registry crimes and escort high-value cargo that cannot be allowed to vanish or be compromised. Their presence is visible but not theatrical. A calm checkpoint that always works is the intended message.

Institutionally they care about throughput and a low incident rate. Individually it varies, because SEA culture prizes competence and clean audits. Pride comes from a route that runs for years without significant disruption. They are important because every other division relies on them to keep the lattice intact. When they do their job well, nobody should notice.

They also manage emergency re-routing and incident arbitration when a sector committee and a hubworld office disagree. In those moments, the SEA acts as the neutral executor of standard, not a political actor. Their power is high in the moment and then it recedes back into procedure.

Legal Code Handbook Use

The Security Enforcement Arm uses the Handbook as its procedural foundation. Each agent carries a compact digital version embedded in their personal devices, allowing instant cross-reference of law during inspections or arrests. The SEA regards it as near absolute written authority, so interpretation on an individual basis is discouraged. Field officers memorize key passages, especially those governing property seizure, arrest protocol, and data integrity.

2. History

The SEA began in the first decade after the war as convoy guards. Scarcity and fragmented control made raids common, so provisional militias were contracted to ride alongside the earliest chain-route caravans. They weren’t professional, they were whoever had weapons and loyalty to a provisioning corps. By 5 CY, these guards evolved into a permanent service directly under the CTA, stripped of faction loyalties and trained in uniform procedure for the most effective strategies.

By 20 CY, raids had largely disappeared, but smuggling and forgery had replaced them. The SEA shifted from armed escorts to auditors with weapons. They began to check manifests, sweep for counterfeit signals, and enforce registry integrity. Over time, they specialized further. By 50 CY, most SEA detachments were trained more in diagnostics, audit procedures, and dispute arbitration than in combat. Their weapons became secondary to their skills.

The SEA’s structure reflects this history, because every detachment still keeps an armed wing, but its reputation is built on being a calm, neutral enforcer of order, descended from a time when starving raiders were the biggest threat. Their legitimacy comes from the memory that when everyone else was looting, they kept the convoys running.

STATION ADMINISTRATORS

GENERAL INFO

Type: Station-level management role

Scope: Daily operations of hub or periphery stations

Appointment: By sector committee, fixed term

1. General Description

A station administrator runs the daily cycle of a hub or periphery station. The job mixes logistics, personnel, maintenance, and diplomacy.

They schedule docking and undocking against chain slots, balance storage against incoming manifests, authorize repairs, and adjudicate disputes between crews.

They coordinate with sector committees for inspections and with SEA detachments for security sweeps. Employment is by committee appointment for a fixed term after a record of clean audits in subordinate roles.

The administrator needs to be calm under constant pressure, have fluency with terminal systems, and enough mechanical literacy to understand when an engineer is asking for time versus trying to hide a fault. They spend their day in motion between terminals, bays, and meeting rooms.

The measure of success is simple: No delays. No spills. No unlogged cargo. No people hurt. They manage a living machine and try to keep it from noticing itself.

2. History

The role of a station administrator evolved from the wartime quartermaster. During the war, each station or convoy had someone responsible for ration lists, docking logs, and maintenance schedules. These roles were informal and rotated among whoever had the literacy and stamina to do the paperwork. After the CTA standardized trade, it formalized the quartermaster role into a permanent, professional office: the station administrator.

By 15-17 CY, every hubworld and periphery station had an administrator appointed by the sector committee, tasked with enforcing CTA schedules. The job became more technical as terminals spread: no longer counting crates by hand, but managing docking slots, ID access, and maintenance through linked systems. Over time, administrators became the backbone of station life, evolving from ration-keepers into full-scale managers of living machines.

STANDARD TERMINAL CODE

GENERAL INFO

Type: Standardized identification and designation system

Purpose: Uniform coding for stations, terminals, camps, vessels, and personnel across CTA space

Introduced: Cycle Year 3

1. Station ID Codes

Format: SYS-###-NODE[ALPHA|BETA|etc]-STN[##]

Example: KR2-715-NODEB-STN04

- SYS: 2–3 letter system code (e.g. KR = Kravin Belt)

- ###: CTA grid reference sector

- NODE: Specific orbital or ground node, often based on original colonization layout

- STN##: Individual station number

Alternatives:

- AUX-STN-9 = Auxiliary CTA station, minor function

- MNT-STN-2 = Maintenance hub station

- CHK-GATE-A = Checkpoint Gate A (often at cargo corridors)

2. Terminal Prefixes

Format: [LOC]-TERM-[TYPE]-[##]

Example: ZIN-TERM-LOG-08

- LOC: 3-letter base abbreviation of zone or planet

- TYPE: Terminal type:

- LOG = Logistics

- ENG = Engineering

- COM = Comms

- MED = Medical

- SEC = Security

- ##: Number based on physical location or install order

Additional Tags:

- XTERM = Deprecated, dangerous, or corrupted terminal

- TERM-CIV = Civilian-access terminal

- TERM-OP = Operator/authorized use only

3. Camp Designations

Format: CTA-CAMP-[ZONE]-[CODE]

Example: CTA-CAMP-RQ4-D1F3

- ZONE: Zone or grid sector code

- CODE: Local alphanumeric assignment; these often degrade into less meaningful codes over time in more remote areas

Informal Naming:

Locals usually call them things like “Ditchpoint,” “Camp Cradle,” “Dryside,” or “Relay Nest 14” based on landmarks, culture, or various other namesakes.

You could add in unofficial signs like:

- “Camp Mercy (CTA-CAMP-X59-H23)”

- “Relay Nest Delta (TERM-ENG-ND2)”

4. Unit/Ship Identifiers

Format: [TYPE]-[CALLSIGN]-[SEQ]

Example: HAULER-VESNA-4427

- TYPE: Role-based prefix:

- HAULER, SCOUT, MEDTRAN, FERRY, POLYFREIGHT, etc.

- CALLSIGN: Custom or assigned by port

- SEQ: Serial number for registry purposes

5. Personnel Badges

Format: ID-[BLOCK]-[TYPE]-###-[CHECK]

Example: ID-KR3-TECH-529-B

- BLOCK: Sector or assignment origin

- TYPE: Role/training background (TECH, LOG, EXO, MED, OBSV, CTRL, EDU)

- CHECK: Letter check for scan verification (often out of date)

6. Degradation

Many of these codes would be partially scratched out, mislabeled, or rewritten with a marker. For example:

- TERM-ENG-ND2 might be labeled on the screen as just E-Term Nest 2

- A shipping crate from KR2-715-NODEB-STN04 might just be tagged “B-Nest / 04 / Kravin” in grease pen.

Additions to the code system made by the CTA may degrade the efficiency of the system and possibly render sections obsolete or broken due to software rot. Some parts of the system that are not used regularly are especially prone to this. The CTA’s goal is efficiency and utility and they rarely go back to fix past issues unless mandated or requested by a majority.

7. History

The standardized terminal code was introduced in 3 CY, after the first large-scale synchronization failures between periphery and Core terminals. Before then, local committees had adapted their own “branch” codes, based on leftover military encryption, corporate shorthand, or even regional dialects.

These systems could not interface cleanly with each other, leading to lost contracts, duplicated credits, and exploitations of inconsistencies.

The CTA responded by developing a universal code set known as the standard terminal code, modeled on a stripped-down lingua franca of pre-war programming languages.

Standard terminal code was designed to be minimal because every command had to be executable on the smallest station terminal as well as on Core-grade archival systems. Its creation emphasized redundancy and verification, forcing every transaction or communication to generate multiple confirmation markers. This slowed processes slightly but eliminated the catastrophic failures of exchange before the invention of standard terminal code.

HAULER-DREV-3349

GENERAL INFO

Type: Spaceship

Place of origin: CTA

History: Used as a cargo hauler before being decommissioned

Current owners: Damir & Marek

1. General Description

The HAULER-DREV-3349 is an old CTA cargo hauler retrofitted into a liveable craft. The vessel is blocky, heavy, with thick plating scarred from years of use. Its interior is functional but cramped. Around half of the parts are scavenged or reverse-engineered. The accommodations onboard are minimal, including sleeping bunks, a small mess, and basic hygiene facilities. Comfort was secondary to hauling capacity. There is a kitchen although it is minimal. Storage space is ample, built for hauling bulk cargo. Damir and Marek partition part of it for personal use, though the majority is reserved for jobs.

The HAULER-DREV-3349 is unique not because it was rare in its class but because it survived long after most of its type were decommissioned. While most bulk haulers of its generation were stripped for parts, scrapped, or lost in accidents, the 3349 remained intact, albeit battered. Its longevity made it valuable for those who wanted a durable, if outdated, vessel that could handle rough chain routes and neglected periphery stations. Its thick hull and modular cargo holds make it adaptable, allowing it to carry anything from agricultural surpluses to industrial salvage.

[CTA VESSEL REGISTRY]

Vessel ID: HAULER-DREV-3349

Model Type: SCR-KL Cargo-Class IV (Decommissioned)

Original Use: Long haul cargo transport

Current Status: Decommissioned, in civilian use

Inspection Date: [Last known: 4 cycle years ago]

Flagged on: 2 occasions for proximity to restricted repair zones without prior permits (resolved)

Damir and Marek currently own and live in the ship. It allows them to sustain themselves independently, hauling goods where contracts take them. Its cargo capacity makes them useful to employers while giving them autonomy.

They live there because it is both home and work. Housing is tied to contracts, and permanent settlement is not an option for them. The ship provides continuity.

It’s barely legal. Technically, ships are work property, not residential zones, but enforcement is lax so long as permits are in order.

2. History

The ship was used as a cargo hauler before being decommissioned. It served for nearly four decades before being deemed unfit. Structural fatigue and outdated systems made it inefficient compared to newer haulers. It carried primarily raw materials and agricultural bulk, though it occasionally carried machinery. Over its decades of use, it developed a reputation as rugged and reliable, though increasingly outdated compared to newer automated haulers.

Damir and Marek acquired the HAULER-DREV-3349 after decommission. They claimed it through a mixture of salvage rights, abandoned paperwork, and persistence.

3. Unique Features

Several aspects have been changed since Damir and Marek acquired it. The ship’s cargo management systems were retrofitted for more flexible storage, enabling them to carry mixed loads instead of standardized crates.

Life-support systems, originally minimal, were patched to allow semi-permanent habitation, including makeshift living quarters, a functional galley, and private workstations.

Its communications array was also retooled, giving it more secure access to chain-route networks than a normal civilian hauler of its age.

Interior Layout

- Bow: Cockpit and comms alcove

- Mid: Bunks, galley, lockers

- Aft: Cargo bay with modular racks, tool bench, parts cage

- Service: Crawl‑tubes to life‑support and reactor shroud

Maintenance Schedule

- Air filters: 30 days

- Hull scan: 90 days

- Reactor inspection: 180 days

- Comms array recal: 60 days or after heavy solar noise

CHAIN ROUTES

GENERAL INFO

Type: Fixed logistical pathways

Scope: Connect periphery stations, hubworlds, and the Core

Primary: 7 main chains + secondary branches

1. General Description

Chain routes are the lifelines of the CTA. They are fixed logistical pathways connecting periphery, hubworlds, and the Core.

There are dozens of routes, but seven “main chains” form the backbone of the CTA. These link each of the seven systems to the Core. Secondary chains branch off them, but the main chains carry the vast majority of goods.

They are the arteries through which all goods, permits, and communications flow. Without chain routes, the centralized economy would collapse into fragmentation.

Unlike older, more flexible routes, chain routes are rigidly standardized and highly monitored. Chain route predictability ensures efficiency but limits spontaneity. They also serve as migration paths, cultural conduits, and secure lines of Authority presence.

For example, imagine a shipment of grain leaving an agricultural hub. The cargo is logged at its point of origin, loaded into a freighter, and then moves along a chain route: first to a periphery station, then handed off at a hubworld, before finally reaching the Core. At each node, terminals confirm the cargo’s status and verify permits. The “chain” is literal because each link ensures the flow continues without break.

Efficiency is calculated through standardized CTA algorithms that weigh distance, energy cost, and stability of the relay network. Adjustments are rare, as routes are meant to be permanent and predictable. A disruption to one route often leads to rerouting along pre-approved alternatives.

Food remains the single most important good. Without steady supplies, urban systems like the Core or hubworlds would collapse. Machinery, permits, and data are also vital, but grain and staple goods underpin everything.

They are also militarized. SEA patrols run constant sweeps, and any unsanctioned signal near a chain is flagged. Entire economies form around areas where chains cross or branch.

On disruption, SEA issues node lockback and broadcasts approved alternates; priority goes to perishables and medical cargo.

Patrols, strict permit checks, and terminal verification ensure disruptions are rare. Smuggling happens, but only at the fringes. The main chains themselves are considered nearly untouchable, not just logistically but symbolically, as breaking one would be an affront to the CTA itself and every other system would be affected (making interference with them too costly to consider).

Chain routes matter because they are the arteries of the CTA. Without them, the system would collapse into scarcity and local collapse.

2. History

Chain routes are designed to prevent this by locking trade into a single system-wide standard, impossible to hijack without tripping CTA oversight. Their existence explains why smuggling and irregular travel remain fringe activities. Anyone with real goods wants them moved on the chain.

Chain routes were established during the CTA’s first century, designed to eliminate redundancy and wasted time in trade. Routes were mapped not just for distance but for security and relay strength. Early on, routes were mapped conservatively, prioritizing secure space near stabilized zones. As confidence grew, the CTA expanded chains into more contested or marginal regions, absorbing them into the system. Over time, the “main chains” became institutionalized, while smaller side chains developed to handle local trade.

Initially, routes were far less efficient, with more redundancy and overlap. As infrastructure improved, the CTA streamlined them, collapsing dozens of smaller paths into fewer, stronger chains. Their rigidity has grown over time, reflecting the Authority’s emphasis on predictability.

The chaos of the war exposed the weakness of fragmented trade routes. Chain routes were explicitly designed as a response: centralized, stable, and unbreakable lines of movement, impossible for local factions to disrupt without facing CTA reprisal.

TERMINALS

GENERAL INFO

Type: Standardized interface device

Place of origin: CTA

Purpose: Communications, transactions, authorizations across CTA space

1. General Description

A terminal is the standardized interface device through which all CTA communications, transactions, and authorizations are carried out. All terminals can use the standard terminal code.

They serve as the primary line of communication between individual workers, managers, and the wider systems of authority. Terminals are highly regulated pieces of equipment, manufactured to uniform specifications to ensure compatibility across all CTA jurisdictions.

Terminals handle data exchange, contract updates, chain broadcasts, and personal identification verification. Depending on clearance, a terminal can authorize transfers, process requests, or display higher-level directives.

While their functionality varies by model, all terminals are built to handle secure communication and cross-system standard codes without corruption.

The most efficient use of terminals is in synchronized chain route broadcasts, where information is delivered simultaneously to hundreds of thousands of devices without delay or corruption.

Terminals communicate through encrypted channels layered across CTA relay networks. They can operate on local connections or long-range inter-system relays depending on their class.

Locally, terminals link directly through short-range encrypted signals. This is most common in administrative offices, where dozens of terminals sync to a single management node. These connections prioritize speed over range, ensuring no lag in contract approvals or permit checks.

Relay networks are layered, primary long-haul relays between hubs, supported by secondary relays for periphery connections. Signals are encrypted, duplicated, and bounced through multiple channels so that disruption in one does not collapse the entire chain.

To prevent systemic failure, terminals use redundancy and failover modes, with analog verification processes in place for critical exchanges.

The most common failure is signal lag or dropped sync with the registry, which freezes transactions momentarily. Hardware rarely breaks, but when it does, it’s usually from physical damage to ports or displays. In extreme cases, memory corruption can make a terminal unable to read an ID.

They are used for everything from clocking into work, logging repair tasks, receiving chain route broadcasts, and approving permits, to accessing archival data. Terminals represent the day-to-day interface with the CTA system, and life under its jurisdiction is nearly impossible without access to one.

Terminal Classes:

- TERM‑CIV: “Terminal, civilian.” Public access. Contracts view, ration claims, queue tickets.

- TERM‑OP: “Terminal, operator.” Operator‑only. Permits, overrides, diagnostics.

- XTERM: Deprecated or compromised. Label indicates restricted access and audit required.

2. History

The first prototypes of terminals predate the CTA, but they became standardized with the Authority’s foundation at 0 CY. Early terminals were clunky and inconsistent, requiring constant adaptation.

The invention of the terminal cannot be traced to one inventor. It was a collective effort by early CTA engineers who synthesized dozens of fractured systems into one. Over time, the CTA mythologized this standardization as an inevitable step in progress, which is more of a cultural symbol than personal credit to any one person.

The CTA unified their design into the present modular format, which has remained largely unchanged due to its reliability.

THE MARKET REGISTRY

GENERAL INFO

Type: Identification system